Alfred Russel Wallace: Back in the picture

|

| Image: Natural History Museum |

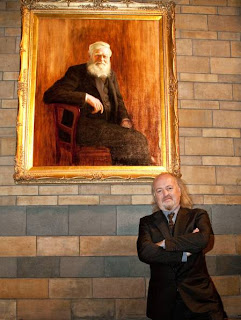

Bailey's two-part documentary on Wallace (part two to be aired on BBC2, this Sunday) comes during Wallace 100, a series of events throughout 2013 to mark the 100th anniversary of his death.

Some, including Bailey, argue that Wallace is a 'forgotten man' of science; his contribution to the Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection having been watered-down or forgotten completely with the passing of time.

Wallace 100 seeks to put that right, not least by returning a portrait of the man to the main hall of the Natural History Museum in London - a portrait that was removed in 1971. Now, Wallace will have a presence in the NHM to rival that of his colleague in science, Charles Darwin.

A fund has also been set up to erect a bronze sculpture of Wallace at the NHM. This sculpture, currently being created, will finally complete an ambition which has existed since Wallace's death but was not realised due to the outbreak of World War 1.

As well as his contribution to the theory of evolution, Wallace is also know as the 'Father of Biogeography' - the study of how and why plants and animals are distributed across the world.

Biogeography, in tandem with evolution, explains why you find kangaroos in Australia and not in Canada; why you find giraffes in the wild in Africa and not in Ireland.

|

| The Wallace Line (in red) marks a dividing line in biogeography |

Wallace's travels and studies in south-east Asia led him to think about how animals and plants are distributed and he was able to draw a line - The Wallace Line - through modern day Indonesia and Borneo to indicate a dividing line between 'Australian-type' flora and fauna on one side and 'Asian-type' plants and animals on the other.

This line, we now know, corresponds with the meeting point of two major tectonic plates which have only (geologically speaking) recently moved together. So, whereas now these two regions lie very close together, the plants and animals on these plates developed in biogeographical isolation and differ hugely from one another. They're the original 'odd-couple'!

Watch the second episode of Bill Bailey's Jungle Hero on BBC Two on 28 April.